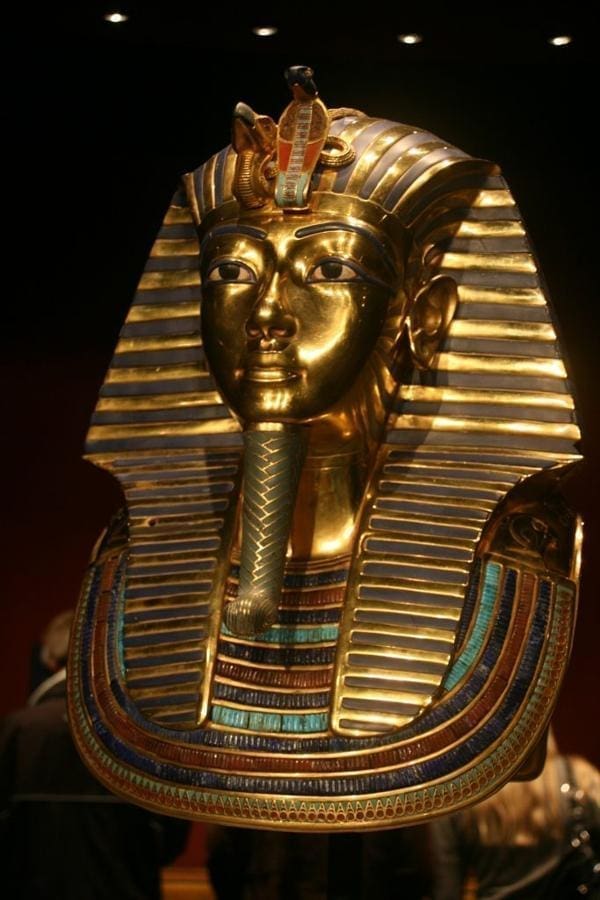

Even the most ancient civilisations had an excellent grasp of the art of gilding: this is evidenced by the refined gold leaf decorations on the sarcophagi and funerary offerings of the pharaohs of ancient Egypt, and the decorations adorning fabrics and wooden and terracotta artefacts in ancient China.

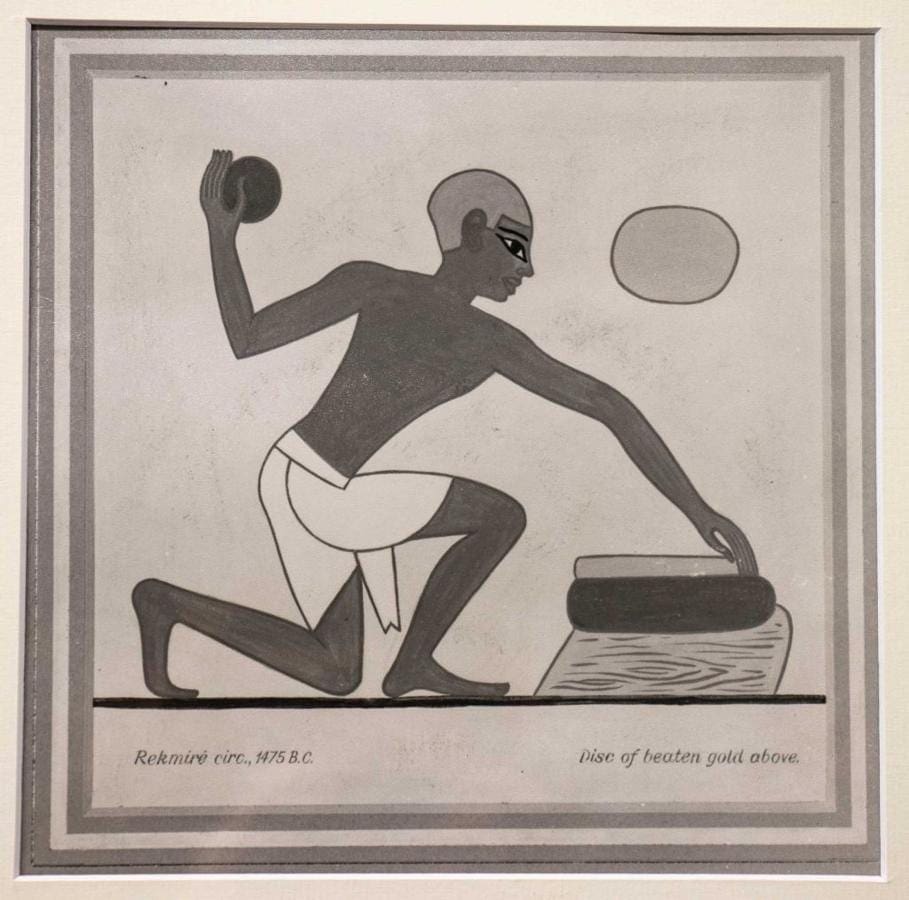

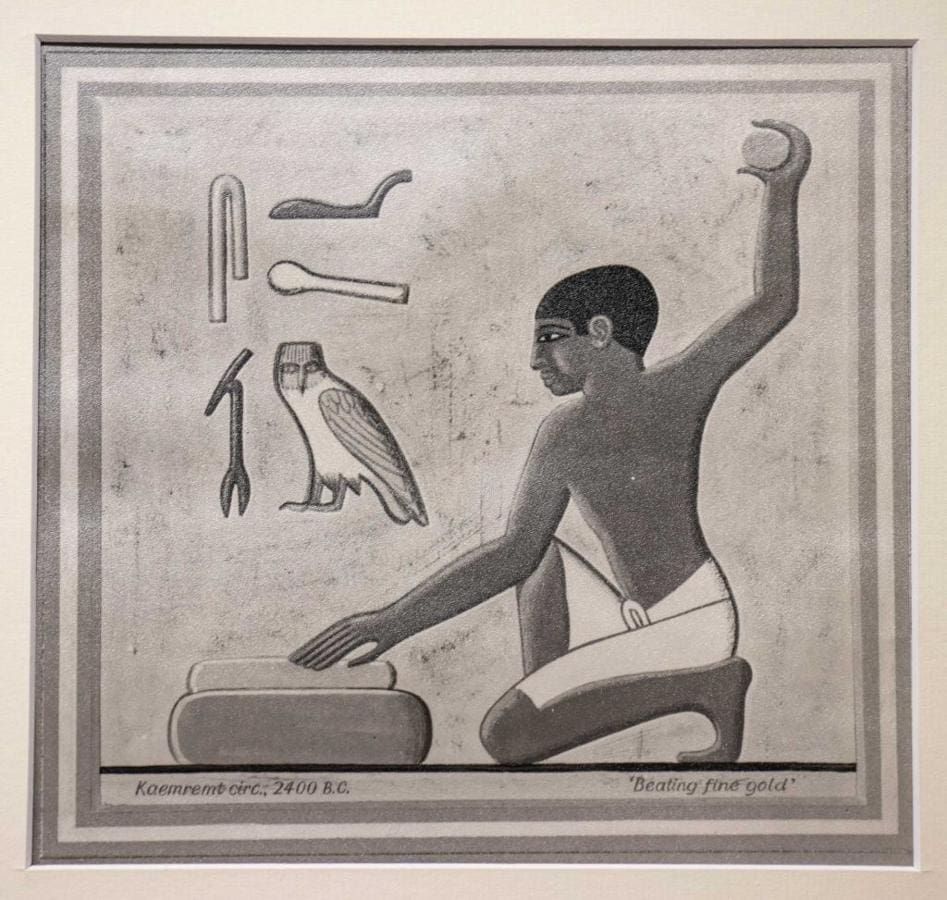

Multiple sources attest to the production of gold leaf in Egypt prior to the 5th Dynasty, and document the technical expertise achieved by gold beaters during the 12th Dynasty (1991-1786 BC), when they managed to produce sheets as thin as 1/1000 mm.

The Greeks decorated their wood, stone and marble sculptures with gold leaf. In the Odyssey, Homer describes Menelaus’ palace as “glittering with gold” and full of the “splendour of the sun and the moon”, and describes that of Alcinous as having golden doors, silver jambs, and gold and silver dog statues that were “immortal and unaging forever.” Diodorus Siculus, on the other hand, said that the temple of Diana in Ephesus was entirely decorated with gold foils. The symbolic value of gold is evident in the writings of both authors: used in both private residences and in places of worship due to its incorruptibility, it is immediately reminiscent of the divine and eternal plane.

During the Hellenistic period, the Greeks gilded metals using a special firing process with mercury amalgam. In fact, this expedient, which was used for the first time in China, remained the most widely-used technique up until 1800.

The Romans used gilding extensively to embellish public and private temples and palaces. Numerous finds from the era have shown that the thin strips of gold (melted in a 10% silver alloy) were applied to a base prepared with plaster or marble powder and glues of animal origin, not much different than the techniques used by gilding craftsmen today.

In 55 AD, Emperor Nero ordered to cover the stone structure of the most important theatre in Rome (the theatre of Pompey) with gold in order to demonstrate his empire’s power to Tiridates, King of Armenia.

Pliny the Elder describes Rome as being adorned with public and private buildings covered with sparkling gold foils and, in his Naturalis Historia, he says: “The ceilings which, at the present day, in private houses even, we see covered with gold, were first gilded in the Capitol, after the destruction of Carthage. From the ceilings this luxuriousness has been since transferred to the arched roofs of buildings, and the party-walls even, which at the present day are gilded like so many articles of plate.” This testimony is important, as it reveals how the practice of gilding was not only used on public buildings, but private ones as well.

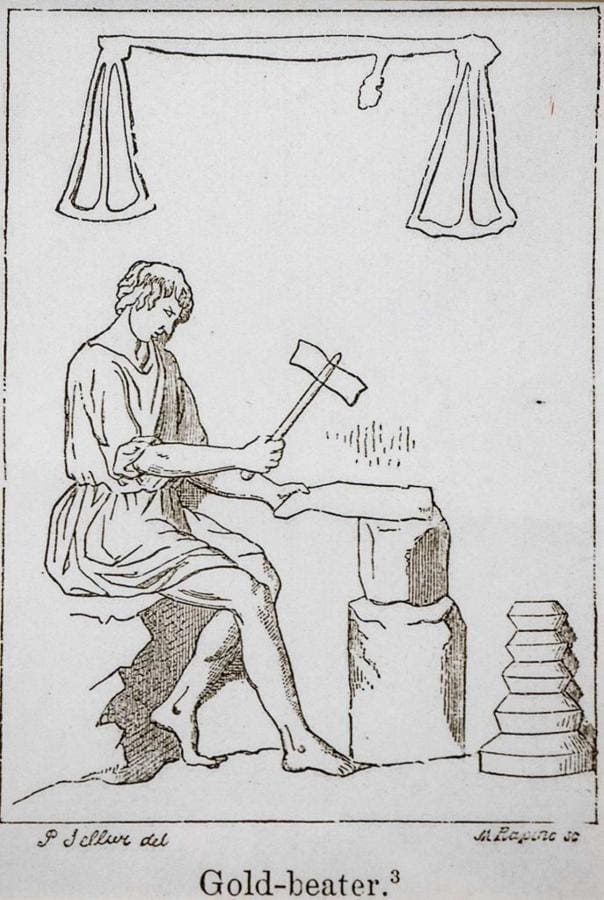

As for the gold beaters who provided the raw materials for all this splendour, the Greek and Latin historians speak repeatedly of their mastery. In Latin, a craftsman who produces gold leaf is associated with the figure of the goldsmith, and is called an aurifex bractearius. Pliny said that one ounce of gold could produce about 750 leaves.

But the fact of the matter is that the historical sources on the gold beating profession in ancient times are fragmented and discontinuous. In order to help is understand how gold leaf was produced, we can refer to the technical literature of the eighth century A.D., which, as numerous studies have shown, draws heavily upon much more ancient sources attributable to the Egyptian priests and alchemists of the late Hellenistic period. Of these texts, the Codex Lucensis 490 is particularly important, as it describes all the steps involved in thinning the gold leaf, starting from the ingot: it explains that the gold strips were beaten – bathed in gold – between copper foils, and notes that 1028 leaves could be produced from ounce of Byzantine gold and one ounce of pure silver.